Breaking the Goldfish Bowl: The DragonGate Eve of Budget viewpoint

Time to reassess the case for Government relocation

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED IN MARCH 2017. GRAPH HAS BEEN UPDATED TO DISPLAY CURRENT CIVIL SERVICE DISTRIBUTION.

In 2004 municipal leaders in the North Italian town of Monza enacted the so-called “Goldfish law” – which prohibited owners from keeping their pet fish in curved goldfish bowls. The reasoning being that, “a fish kept in a bowl has a distorted view of reality…and suffers because of this”.

In the same year Gordon Brown greenlit the Lyons Relocation programme- a programme to move 20,000 civil servants away from Whitehall and into the regions – a process partly driven by cost savings and regeneration but also to forge a closer connection between policy bodies and the communities they serve. With the possible compassionate impact of putting civil service goldfish into tanks that would allow a less rounded, but more real understanding, into the impact of national policy decisions at the grass roots.

Since the reversal of the 2004-9 relocation programme the current plans for central government activity have focused upon estates and business modernisation with all future planning fixated in London and only the most metropolitan of the regional capitals.

Current strategy is epitomised by HMRC’s Building Our Future (BoF) programme.

BoF aims to rationalise approximately 170 tax centres into 13 super-hubs and four specialist sites – and has the ability to further destabilise fragile economies who have been long term bases for the department such as Southend on Sea (1,200 FTEs), Bradford (2,000 redundancies expected by 2021) and Sunderland (3,030 FTEs).

This is but one example of the rationalisation plans taking place across the 28 Government Departments supervised by the property focused Government Property Unit (GPU).

The current Civil Service agenda for modernisation shows little confidence in the skills, quality of lifestyle and place-based opportunities that non-metropolitan locations can provide.

This is despite the fact that historically the UK has entrusted its signals intelligence Headquarters to Cheltenham (GCHQ), Government statistics and the manufacture of its currency to South Wales (ONS and the Royal Mint in Newport and Cardiff respectively) and the weather forecast (Met Office) to Devon.

The impact of basing these stand-alone quangos in relatively remote, non-metropolitan locations has not diminished returns in any way and has delivered disproportionately positive economic impacts to their localities. Interestingly, each of these relocations has resulted from laissez-faire business planning by the respective agencies, and not as a consequence of central direction.

Despite former Cabinet Office Minister Francis Maude having promised a ‘Bonfire of the Quangos’ on behalf of the then Coalition, since 2010 every newly formed Quango and Agency (there have been 38 in total) from the Green Investment Bank to NHS Property Services has been headquartered in London.

This includes the Government Digital Service (GDS), whose very mantra is “Digital by Default”- that the public sector should be able to deliver services from anywhere on the planet. The circular argument is that new Government activity must be sited where existing Government and FTSE 100 private sector stakeholders are already.

This results in new offshoots of Government and private sector HQs cramming themselves ever closer to the ‘black hole’ of Whitehall – which is beginning to creak under the weight of its compressed mass – all the while competing with a vastly overheated central London recruitment and property market.

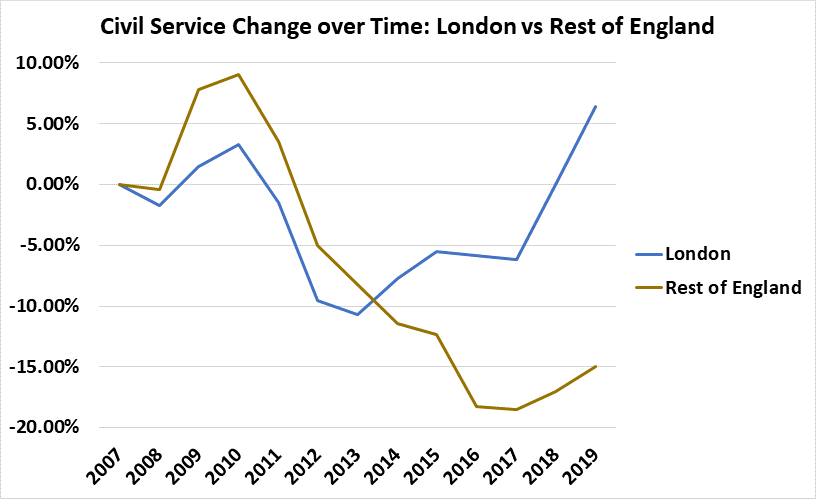

The evidence for this is striking. Since the global downturn every region across the UK has seen civil service numbers drop as both a percentage and as an overall number – apart from London where the civil service has risen and become in effect a high-growth sector.

Location is not just about what the regions are missing, it also contributes to the closely confined mindset that imprisons the mandarin away from place-based thinking, genuine partnership working as opposed to diktat and fuels inter-departmental turf wars.

The current property vision espoused by the GPU is for a network of no more than 20 super-hubs to cover all Government departments – with the gravitational well still firmly set in London. The remainder are to be no more than a five-minute walk from train terminals of regional centres such Leeds, Manchester, and Birmingham – clustered in barracks of other civil service agencies with no involvement from the wider public sector, including from local government.

This creates the depressing prospect that the majority of the future civil service workforce will spend their time working in super clusters of other civil servants and alternately ploughing through spreadsheets and position papers on train journeys that will deposit them to other sanitised, identikit environments positioned close enough to train stations to avoid the general public and certainly wider public services.

Effectively, as a form of inward investment, public sector relocation can have a significant impact on local economies. For instance, the relocation of parts of the BBC to MediaCityUK in Salford has not just regenerated the area, but also attracted its supply chain and similar businesses to co-locate. Public sector relocation brings with it a substantial multiplier.

Similarly, the relocation of a significant part of the Ministry of Defence to Abbey Wood, Bristol some 20 years ago has attracted several thousand private sector jobs.[1] It also creates significant long-term efficiency savings, since office floor space is generally much cheaper outside of London.

We believe public sector relocation should form a distinct part of the industrial strategy, catalysing thematic clustering in a number of places across the country.

As part of this process, places should be proactive in establishing public service hubs for parts of the public sector to relocate to. For instance, in a joint venture with the developer Siglion, Sunderland City Council is speculatively redeveloping new office space at the former Vaux brewery site.[2]

Because the upfront cost of relocation is expensive – though ultimately repaid within several years in most cases – places may also be required to make some contribution, be that through capital funding, land or the management of the planning process.

As a guiding rule, Government should only relocate public sector functions to areas with a critical population mass of 100,000, to sites within close proximity of a railway station and where local labour supply can meet recruitment needs (primarily in administrative support and junior managers).[3] Furthermore, an economic deprivation factor should be embedded within any new strategy.

It is our contention that whilst the civil service are being increasingly isolated in the name of “business transformation” a very obvious opportunity for reinvigorating communities and developing genuine partnership approaches to place is being missed. The current strategy of creating superhub goldfish bowls – may join up central government and enable business transformation- but will provide little perspective between the centre and the communities they serve.

Furthermore, where we suggest in the relocation of government departments, only civil servants who have face-to-face interaction with ministers should remain in Whitehall. For organisations such as NDPBs, pied-a-terre spaces should be provided for senior staff who need to interact with senior civil servants, ministers and other politicians.

Strong stuff for many I’m sure – but we will live in disruptive times.

This article appeared in LinkedIn Pulse:

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/breaking-goldfish-bowl-dragongate-eve-budget-time-reassess-werran